2023 Earth Overshoot Day – 2 August

Editor’s note: The problem is not climate disruption. The problem is overconsumption that is overpowering nature’s systems, the consequence of which is climate disruption – and even more significantly – biodiversity loss and extinctions of our very life-support systems.

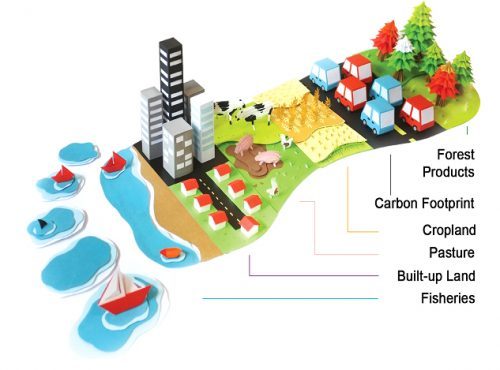

“This year, Earth Overshoot Day lands on August 2. Earth Overshoot Day marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year. If a population’s demand for ecological assets exceeds the supply, that region runs an ecological deficit, liquidating its own ecological assets (such as overfishing), and/or emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Earth Overshoot Day is computed by dividing the planet’s biocapacity (the amount of ecological resources Earth is able to generate that year), by humanity’s Ecological Footprint (humanity’s demand of resources for that year), and multiplying by 365, the number of days in a year. Both measures are expressed in global hectares. It is calculated by Global Footprint Network, an international research organization, to help the human economy operate within Earth’s ecological limits.” More at – About Earth Overshoot Day, and Earth Overshoot Day.

“This year, Earth Overshoot Day lands on August 2. Earth Overshoot Day marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year. If a population’s demand for ecological assets exceeds the supply, that region runs an ecological deficit, liquidating its own ecological assets (such as overfishing), and/or emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Earth Overshoot Day is computed by dividing the planet’s biocapacity (the amount of ecological resources Earth is able to generate that year), by humanity’s Ecological Footprint (humanity’s demand of resources for that year), and multiplying by 365, the number of days in a year. Both measures are expressed in global hectares. It is calculated by Global Footprint Network, an international research organization, to help the human economy operate within Earth’s ecological limits.” More at – About Earth Overshoot Day, and Earth Overshoot Day.

Earth’s life support has 9 boundaries: climate is but one

“All life on Earth, and human civilization, is sustained by vital biogeochemical systems, which are in delicate balance. However, rapid population growth and explosive consumption is destabilizing these Earth processes, endangering the stability of the safe operating space for humanity. Scientists note nine planetary boundaries beyond which we can’t push Earth Systems without putting our societies at risk: climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol pollution, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, land-system change, and release of novel chemicals. Humanity is already existing outside the safe operating space for at least four of the nine boundaries: climate change, biodiversity, land-system change, and biogeochemical flows. Unfortunately for us, climate change represents just one of nine critical planetary boundaries which our imprudent actions risk overshooting.” More at – The nine boundaries humanity must respect to keep the planet habitable | Mongabay.

“All life on Earth, and human civilization, is sustained by vital biogeochemical systems, which are in delicate balance. However, rapid population growth and explosive consumption is destabilizing these Earth processes, endangering the stability of the safe operating space for humanity. Scientists note nine planetary boundaries beyond which we can’t push Earth Systems without putting our societies at risk: climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol pollution, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, land-system change, and release of novel chemicals. Humanity is already existing outside the safe operating space for at least four of the nine boundaries: climate change, biodiversity, land-system change, and biogeochemical flows. Unfortunately for us, climate change represents just one of nine critical planetary boundaries which our imprudent actions risk overshooting.” More at – The nine boundaries humanity must respect to keep the planet habitable | Mongabay.

Human made stuff now outweighs all of Earth’s biomass

“In a startling sign of the impact that humans are having on our planet, a study published in the journal Nature estimated that 2020 marks the point when human-made materials outweigh the total mass of Earth’s living biomass. Materials such as concrete, steel and asphalt have increased rapidly since 1900, when they made up the equivalent of just 3% of the mass of living biomass — plants, animals, and microorganisms. The mass of human-produced materials has grown from less than 0.1 teratonnes to roughly 1 teratonne (1 trillion tonnes), doubling every 20 years for the last century. Today, according to the study, all the living plants on Earth weigh roughly 1 teratonne, half of what they did when the agricultural revolution began 12,000 years ago. Plants account for 90% of the Earth’s living biomass, per the study.

“If current trends continue, human-produced materials will weigh triple the total mass of living biomass by 2040, according to the study. We’re using up primary resources at such an unsustainable pace that we may be ‘irreversibly’ depleting some of them ― and subverting our life support systems in the process. These findings are further evidence that we are living through a new geological era in which human activity is the dominant force shaping Earth’s climate and environment, which scientists have dubbed the Anthropocene.

“According to a United Nations report, in 1970, about 22 billion tons of primary materials were extracted from the Earth, ballooning to 70 billion tons by 2010. At that rate we’ll need 180 billion tons of extracted materials annually to meet demand by 2050. Dire environmental consequences include: higher levels of acidification and eutrophication of soils and water bodies, increased biodiversity loss, more soil erosion, and increasing amounts of waste and pollution (especially climate emissions).” More at – As of 2020, Human-Made Materials Outweigh Living Things | Time, and Our Consumption Of Earth’s Natural Resources Has More Than Tripled In 40 Years | HuffPost.

Overconsumption = resource extraction = ecosystem collapse

“The global economic system is a Ponzi scheme, an utterly unsustainable system that effectively takes wealth from our children and future generations — wealth in the form of ground water, arable land, fisheries, a livable climate — to prop up our carbon-intensive lifestyles. We cannot stop catastrophic climate change without a pretty dramatic change to our overconsumption-based economic system. We have already overshot the Earth’s biocapacity — and the overshoot gets worse every year. ‘A quarter of the energy we use is just in our crap’, physicist Saul Griffith explains. The end to hyper-consumerism is not something amenable to legislation. It is most likely to come when we are desperate — when the reality that we are destroying a livable climate is so painful that we give it up voluntarily, albeit reluctantly.

“A recent must-read New York Times opinion piece, Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene, explains: The human psyche naturally rebels against the idea of its end. Likewise, civilizations have throughout history marched blindly toward disaster, because it is unnatural for us to think that this way of life, this present moment, this order of things is not stable and permanent. The choice is a clear one. We can continue acting as if tomorrow will be just like yesterday. Or we can learn to see each day as the death of what came before, freeing ourselves to deal with whatever problems the present offers without attachment or fear.” More at – Is Every Day Black Friday? How Climate Inaction And Hypermaterialism Betray Our Children | Think Progress.

Save biodiversity, save the climate, shrink the economy

One of the more insightful thinkers today is Andrew Nikiforuk at the Canadian environmental journal, The Tyee. His essential message is we can’t grow ourselves out of an overconsumptive economy. We have to scale back. He writes: “A number of brilliant energy critics from Vaclav Smil to William Rees have done the figuring, acknowledged the physical limits of things, and told us the truth.  We must contract the global economy, restructure technological society, and restore what’s left of natural ecosystems if we want to live and breathe”. The principal problem is the destruction of biodiversity by the technosphere, a parasitic growth on the biosphere that consumes fossil fuels to drive economic and human growth. This includes a fossil fuel-driven build-out of wind and solar tech.

We must contract the global economy, restructure technological society, and restore what’s left of natural ecosystems if we want to live and breathe”. The principal problem is the destruction of biodiversity by the technosphere, a parasitic growth on the biosphere that consumes fossil fuels to drive economic and human growth. This includes a fossil fuel-driven build-out of wind and solar tech.

Nikiforuk continues: “The appeal of the ‘tech will save us’ charade crosses ideological lines. Both Green New Dealers and the Business-as-Usual Crowd believe a variety of so-called green technologies will save the day”. But Smil has argued that our civilization needs to power down, practice conservation, and set limits on how much stuff it consumes. Of course conventional thinkers worry that means going back to the Dark Ages. Not so. “Our high-tech and high energy civilization contains so much slack and fat that we could easily reduce our energy spending to levels common in the 1960s and 1970s”, writes Nikiforuk. Smil has said “I could design you the global system today without any horrible loss of standard of living, consuming 30, 40, 50% less of everything that we are consuming”. More at – Tech Won’t Save Us. Shrinking Consumption Will | The Tyee, and Returning to a 1970s Economy Could Save Our Future | The Tyee.

Sufficiency before efficiency

“Sufficiency, often also referred to as frugality, starts with consumer behaviour. A sufficient lifestyle means being frugal with the available resources, without reducing one’s own level of satisfaction and quality of life. Only by combining efficiency and sufficiency measures can sustainable development be driven forward and greenhouse gas emissions reduced. This is because any improvements in efficiency are nullified if sufficiency is not taken into consideration.

“Samuel Alexander of the Simplicity Institute used the subhead ‘efficiency without sufficiency is lost’ in his paper A Critique of Techno-Optimism. Making things more efficient is not enough. We have to ask ourselves what we really need — what is enough? I often used the simple clothesline instead of a dryer as an example, or a bicycle instead of a car. Alexander explains that efficiency gains that take place within a growth-orientated economy tend to be negated by further growth, resulting in an overall increase in resource and energy consumption.

“Given the alarms being raised by climate science, high-consumption societies cannot achieve ecological healing unless we practice an unprecedented degree of collective restraint in resource use. Adapting to that new reality will require that we set aside the pursuit of growth.

“Discussing individual consumption or the idea of sufficiency is not taken seriously in North America, but it is in Finland, the source of the 1.5 degree lifestyle report. The Finns even have a movement, Kohtuusliike (or moderation), devoted to sufficiency. The report gets really interesting with policies to promote sufficiency. For instance, a regulatory approach might be to limit the use of private cars. The economic approach might be to apply carbon taxes. The nudging approach would be to build great bike lanes. Cooperation might be to set up sharing and collaborative consumption. An information approach might be labeling of high-carbon products.” More at – What is sufficiency? | My Climate, and Efficiency Without Sufficiency Is Lost | Treehugger, and What Is Enough? | YES! Magazine, and Enough Already: Why Sufficiency Matters | Treehugger.

Curbing consumption through lifestyle adjustments

“Perhaps the more exciting side of permaculture is making stuff. ‘This is my rain barrel! These are my new solar panels!’ That said, the idea of curbing consumption is likely as relevant, if not more so. It is certainly central to a permaculture lifestyle. Ultimately, we are trying to minimize our negative impact on the environment. One of the easier ways of illustrating this point is looking at renewable energy systems. The solution is not to add more solar panels and storage batteries to provide the amount of energy currently consumed; rather, it’s to lessen the energy demand.

Some things that consume a lot energy are totally avoidable — for example, hanging clothes to dry instead of using a tumble dryer. Of course, the dryer is but one electrical appliance in a sea of others. How many can we replace with manual counterparts? The coffeemaker, the vacuum cleaner, the can opener — basically, anything people managed to do before everything became electrified. Sure, some things add unparalleled convenience, such as a freezer in the summer or a water pump, but there are many ways we can reduce our consumption with just minor lifestyle changes.” More at – Cutting Back on Consumption | Permaculture Research Institute.

Some things that consume a lot energy are totally avoidable — for example, hanging clothes to dry instead of using a tumble dryer. Of course, the dryer is but one electrical appliance in a sea of others. How many can we replace with manual counterparts? The coffeemaker, the vacuum cleaner, the can opener — basically, anything people managed to do before everything became electrified. Sure, some things add unparalleled convenience, such as a freezer in the summer or a water pump, but there are many ways we can reduce our consumption with just minor lifestyle changes.” More at – Cutting Back on Consumption | Permaculture Research Institute.

Curbing consumption through low tech innovations

“We’ve gotten used to the pace of technological change exceeding our ability to adapt to it, much less to control it. Every technology has unintended consequences, which society should investigate before widespread adoption of a given technology — a notion known as the precautionary principle. We should start by asking: ‘How much energy does it actually take to lead happy lives’. We need more low tech tools — ones that use less energy, and depend on local skills and supply chains.

“Low-tech does not mean a return to medieval ways of living. But it does demand more discernment in our choice of technologies. British economist E.F. Schumacher’s 1973 book Small is Beautiful presented a powerful critique of modern technology and its depletion of resources like fossil fuels. Schumacher’s mantle has been taken up by a growing movement calling itself ‘low-tech’. Belgian writer Kris de Dekker’s online Low-Tech Magazine has been cataloguing low-tech solutions since 2007.

In the US, architect and academic Julia Watson’s book Lo-TEK (where TEK stands for Traditional Ecological Knowledge) explores traditional technologies from using reeds as building materials to creating wetlands for wastewater treatment. And in France, engineer Philippe Bihouix’s realization of technology’s drain on resources led to his prize-winning book The Age of Low Tech. As Bihouix writes: A reduction in consumption could make it quickly possible to rediscover the many simple, poetic, philosophical joys of a revitalised natural world.

In the US, architect and academic Julia Watson’s book Lo-TEK (where TEK stands for Traditional Ecological Knowledge) explores traditional technologies from using reeds as building materials to creating wetlands for wastewater treatment. And in France, engineer Philippe Bihouix’s realization of technology’s drain on resources led to his prize-winning book The Age of Low Tech. As Bihouix writes: A reduction in consumption could make it quickly possible to rediscover the many simple, poetic, philosophical joys of a revitalised natural world.

“In some places, the principles of low-tech are already influencing urban design and industrial policy. Examples include ’15 minute walkable cities’ where shops and other amenities are easily accessible to residents, using cargo bikes instead of cars or vans for deliveries, and encouraging repairable products through right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US.

“The negative environmental impact of technology is almost invisible in western countries. The externalities stemming from the consumerist system happen in other countries, such as the textile industry, the extraction of rare-earth elements in China, and the extraction of silver in South America. The illusion of a never-ending increase in production is now facing the reality of resource scarcity. 10% of the world’s primary energy is used to extract and refine metals: because of these diminishing returns, the economy will need even more energy, and produce even more CO2 and waste. To overcome resource scarcity, the rise of renewables seems to be an obvious answer. Still, wind turbines, solar panels or electric batteries are made of rare metals that are not renewable. Less than 1% of small metal components of high-tech products are recycled: the rest of them are too difficult to recycle to be cost-effective.

“The negative environmental impact of technology is almost invisible in western countries. The externalities stemming from the consumerist system happen in other countries, such as the textile industry, the extraction of rare-earth elements in China, and the extraction of silver in South America. The illusion of a never-ending increase in production is now facing the reality of resource scarcity. 10% of the world’s primary energy is used to extract and refine metals: because of these diminishing returns, the economy will need even more energy, and produce even more CO2 and waste. To overcome resource scarcity, the rise of renewables seems to be an obvious answer. Still, wind turbines, solar panels or electric batteries are made of rare metals that are not renewable. Less than 1% of small metal components of high-tech products are recycled: the rest of them are too difficult to recycle to be cost-effective.

“Philippe Bihouix gives three principles that can foster ‘low-technology’ solutions for a low-carbon future. Make recycling easy: engineers should avoid complex alloys to allow the recycling of most of the components. Make products more robust and repairable: the ‘throw-away society’ is detrimental to the environment. Use legislation to promote more sustainable development: banning plastic bags, standardizing bottle sizes and shapes and making them returnable would be simple steps towards a less energy-intensive economy.” More at – Power: Limits & Prospects for Human Survival | New Society, and Low-technology: why sustainability doesn’t have to depend on high-tech solutions | The Conversation, and Low-Tech is the new High-Tech | Foresight.

Curbing consumption through community actions

“Annie Leonard of the Story of Stuff Project says “The problems we’ve been solving are not the problems that most need solving. So much focus has gone into faster, cheaper, newer that we actually lost ground on safer, healthier, and more fair. It’s as if we’re getting better and better at playing the wrong game. Our economy was designed by people to get everyone to play by certain rules. The first lesson is to find out what it means to win a game, and that guides every decision you make along the way. So naturally what most people pursue in the economy game is a simple goal – which is ‘MORE’. More money being spent, more roads being built, more malls being opened, and more stuff. That’s what economists call growth. So we take all the money spent on stuff that makes life better (like hospitals), and all the money spent on stuff that makes life worse (like weapons), and we add it together into one big number called GDP.

“We’re told that a bigger GDP means we’re winning. But there’ a big difference between more kids in school and more kids in jail, more windmills or more coal fired power plants, more efficient transit or more gas wasting traffic jams. But in this game of ‘more’, they’re counted the same. Now we can’t change just one rule or one player at a time. The problem is the goal itself – that of MORE. We need solutions that change that. What if we built this game around the goal of ‘BETTER’? Better education, better health, better stuff. To do that, we have to be able to tell the difference between a game-changing solution, or just a new way of playing that old game of ‘more’.” Videos at – The Story of Solutions, and The Story Of Stuff.

Recent Comments